From TRPO to Modern LLM RL Algorithms

Reinforcement learning has become an essential paradigm for large language model post-training. This post traces the algorithmic lineage from classic policy gradients through TRPO and PPO, then into the recent wave of LLM-specific variants: GRPO, Dr. GRPO, GSPO, and CISPO. The goal is to build intuition for why each method exists and what problem it solves.

Policy Gradient

Before diving into TRPO, let’s first revisit the classic policy gradient setup and why naïve updates can be problematic. We work with an infinite-horizon discounted MDP. A trajectory is $\tau=(s_0,a_0,s_1,a_1,\dots)$, generated by the policy $\pi_\theta(a\mid s)$ and dynamics $P(s’\mid s,a)$: $s_0\sim \rho_0$, $a_t\sim \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid s_t)$, $s_{t+1}\sim P(\cdot\mid s_t,a_t)$.

Define the return of a trajectory by $R(\tau)=\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r(s_t)$ and the objective

\[J(\pi_\theta)=\mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim p_{\pi_\theta}}[R(\tau)].\]Our goal is to find $\theta$ that maximizes $J(\pi_\theta)$.

Using the log-likelihood trick, we obtain:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta) =\nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim p_{\pi_\theta}}[R(\tau)] =\mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim p_{\pi_\theta}}\Bigg[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t\mid s_t)\;R(\tau)\Bigg].\]Subtracting a baseline $b(s_t)$ independent of $a_t$ reduces variance while preserving unbiasedness:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta) =\mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim p_{\pi_\theta}}\Bigg[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t\mid s_t)\;\big(G_t-b(s_t)\big)\Bigg], \quad G_t=\sum_{l=0}^\infty \gamma^l r(s_{t+l}).\]With $b(s)=V^{\pi_\theta}(s)$, the bracketed term becomes the advantage $A^{\pi_\theta}(s_t,a_t)$, yielding the common form:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta)=\mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim p_{\pi_\theta}}\Bigg[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t\mid s_t)\;A^{\pi_\theta}(s_t,a_t)\Bigg].\]The problem: The expectations above are taken under the current policy-induced trajectory distribution $p_{\pi_\theta}$. After updating $\theta$, these distributions change, so large steps can make the gradient-based objective a poor proxy for $J$. If we only have trajectories from an old policy $\pi_{\text{old}}$, how far can we move while still making reliable progress?

Trust Region Policy Optimization

While it is difficult to directly compute the true objective $J(\pi)$ for an arbitrary new policy, TRPO introduces a surrogate objective $L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)$ that can be used to lower-bound $J(\pi)$, without sampling new trajectories with $\pi$.

Local surrogate: Evaluating new actions at old states.

Let $\rho^{\pi}(s) = \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t P(s_t = s \mid \pi)$ denote the discounted state visitation distribution under policy $\pi$. The surrogate objective is:

\[L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi) =J(\pi_{\text{old}})+\sum_{s}\rho^{\pi_{\text{old}}}(s)\sum_{a}\pi(a\mid s)\,A^{\pi_{\text{old}}}(s,a).\]The key insight is that everything in this expression can be computed from old trajectories: we sample states from $\rho^{\pi_{\text{old}}}$, use the old policy’s value estimates to compute $A^{\pi_{\text{old}}}$, and only need to query the new policy $\pi(a\mid s)$ for action probabilities. No new rollouts required.

Theorem 1 (Eqn. 9 in the TRPO paper): Pessimistic lower bound with a KL penalty.

TRPO establishes the following bound:

\[J(\pi)\ \ge\ L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)\ -\ C\,D_{\mathrm{KL}}^{\max}(\pi_{\text{old}},\pi),\]where

\[D_{\mathrm{KL}}^{\max}(\pi_{\text{old}},\pi)=\max_s D_{\mathrm{KL}}\big(\pi_{\text{old}}(\cdot\mid s)\,\|\,\pi(\cdot\mid s)\big), \quad C=\frac{4\,\epsilon\,\gamma}{(1-\gamma)^2},\quad \epsilon=\max_{s,a}\lvert A^{\pi_{\text{old}}}(s,a)\rvert.\]This bound shows that $L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)$ minus a divergence-proportional penalty is a conservative lower bound on $J(\pi)$.

This may look mysterious at first glance, but we will show where it comes from in the following section.

Understanding the Surrogate Objective

Now that we have stated the main result, let’s unpack where the surrogate objective $L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)$ comes from. We first establish an exact identity relating the performance of any two policies, then show how replacing one distribution with another gives rise to the surrogate, and finally explain how Theorem 1 guarantees monotonic improvement.

Performance Difference Identity

A standard decomposition (TRPO Eq. 2) expresses the return of a new policy in terms of the old policy’s advantage accumulated along trajectories of the new policy:

\[J(\pi)=J(\pi_{\text{old}})+\sum_{s}\rho^{\pi}(s)\sum_{a}\pi(a\mid s)\,A^{\pi_{\text{old}}}(s,a).\]Intuition: At each state, we compute “how much better than the old baseline this action is”, i.e., the advantage $A^{\pi_{\text{old}}}(s_t,a_t)$. Summing these advantage terms (discounted) over the new trajectory tells us exactly how much the new policy improves over the old one.

This expression is exact but still depends on the new state distribution $\rho^{\pi}$, which we cannot compute without actually rolling out $\pi$.

Using Old Trajectories as a Proxy

To circumvent this issue, the surrogate $L_{\pi_\text{old}}$ uses the state distribution fixed at what we observed under $\pi_{\text{old}}$. Comparing the identity above with the definition of $L_{\pi_\text{old}}$, the only difference is whether states are sampled from $\rho^\pi$ or $\rho^{\pi_\text{old}}$.

This is a reasonable approximation when $\pi$ is not too far from $\pi_\text{old}$. The gap between $J(\pi)$ and $L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)$ arises purely from the state-distribution shift $\rho^{\pi}-\rho^{\pi_{\text{old}}}$. If we restrict updates so that $\pi$ stays close to $\pi_{\text{old}}$ (in a suitable divergence), then the induced shift in state distribution is small, and the surrogate remains faithful.

Formally, Kakade and Langford, 2002 first analyzed how accurate this approximation is under certain policy parameterizations. TRPO modified their result to obtain a slightly looser but simpler bound, leading to Theorem 1 in the TRPO paper.

Monotonic Improvement Guarantee

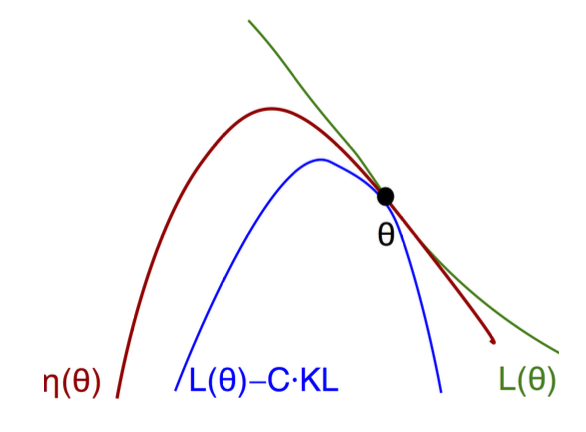

We can show that improving the right-hand side of Theorem 1, i.e.,

\[M_{\pi_\text{old}}(\pi)=L_{\pi_{\text{old}}}(\pi)\ -\ C\,D_{\mathrm{KL}}^{\max}(\pi_{\text{old}},\pi),\]guarantees that the true objective $J(\pi)$ improves at least as much.

By Theorem 1: $\quad J(\pi) \ge M_{\pi_\text{old}}(\pi)$

At equality: $\quad J(\pi_\text{old}) = M_{\pi_\text{old}}(\pi_\text{old})$

Subtracting: $\quad J(\pi) - J(\pi_\text{old}) \ge M_{\pi_\text{old}}(\pi) - M_{\pi_\text{old}}(\pi_\text{old})$

Takeaway

The core insight of TRPO is that as long as the new policy remains within a trust region (measured by KL divergence), the state distribution shift is bounded and we can safely optimize the surrogate objective. This yields a constrained optimization problem (Eqn. 11 in the TRPO paper), which TRPO solves via conjugate gradients and line search.

Proximal Policy Optimization

In practice, enforcing the hard KL constraint is computationally expensive. This motivates Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which replaces the constraint with a simpler clipped objective, achieving similar stability with much less overhead.

Let the importance ratio be

\[r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\mid s_t)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(a_t\mid s_t)}.\]The clipped surrogate is

\[L^{\text{CLIP}}_t(\theta) = \min\Big[r_t(\theta) A_t,\text{clip}\big(r_t(\theta),1-\epsilon,1+\epsilon\big)A_t \Big]\]What does the clip do?

- For $A_t>0$ (good action): encourage increasing its probability, but stop once $r_t>1+\epsilon$.

- For $A_t<0$ (bad action): encourage decreasing its probability, but stop once $r_t<1-\epsilon$.

Interpretation. Inside the clip range, PPO matches the surrogate PG gradient; once a sample has pushed probability “far enough” in the helpful direction (beyond $1\pm\epsilon$), its contribution is zero.

From PPO to LLM Training

PPO was designed for traditional RL environments, e.g., games, robotics, simulations, where rewards arrive at every step and episodes are relatively short. Training large language models introduces distinct challenges. As a result, a family of PPO-style algorithms adapted for language models were proposed. Each retains the core idea—optimize a clipped surrogate using trajectories from $\pi_{\text{old}}$, but rethinks where ratios and advantages are computed and what gets clipped.

GRPO: Group Relative Policy Optimization

Motivation. PPO’s default actor–critic implementation is heavy at LLM scale, and token-level advantages are noisy when rewards are sequence-level. GRPO drops the critic and uses a group-relative baseline from $G$ responses to the same prompt.

Objective (sequence reward, token ratios). For a prompt $x$, sample a group of responses $y^{(i)}$ and get scalar rewards $R^{(i)}=R(x,y^{(i)})$. Define a group-normalized advantage

\[\hat A^{(i)} \;=\; \frac{R^{(i)} - \frac{1}{G}\sum_{j=1}^G R^{(j)}}{\operatorname{std}\{R^{(j)}\}_{j=1}^G},\]The advantage is shared by all tokens in $y^{(i)}$. Each token has its importance ratio:

\[r_{i,t}(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(y^{(i)}_t\mid x,y^{(i)}_{<t})}{\pi_{\text{old}}(y^{(i)}_t\mid x,y^{(i)}_{<t})}\]Therefore, GRPO maximizes a PPO-like clipped surrogate (plus an optional KL-to-reference regularizer). This removes the value net, cuts memory/compute, and fits verifier-style rewards.

\[\begin{aligned} J_{\text{GRPO}}(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{\,q \sim P(Q),\, (o_i)_{i=1}^G \sim \pi_{\text{old}}(\cdot \mid q)} \Bigg[ \frac{1}{G} \sum_{i=1}^G \Bigg( \frac{1}{|o_i|} \sum_{t=1}^{|o_i|} \min\Big( r_{i,t}(\theta)\,\hat A_{i,t},\; \operatorname{clip}(r_{i,t}(\theta),\,1-\epsilon,\,1+\epsilon)\,\hat A_{i,t} \Big) \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad - \beta\, D_{\mathrm{KL}}(\pi_\theta \,\|\, \pi_{\mathrm{ref}}) \Bigg) \Bigg]. \end{aligned}\]Dr. GRPO: “GRPO Done Right”

Motivation. The original GRPO objective introduces optimization bias that artificially increases response length (especially for incorrect outputs). Two culprits identified are (i) length normalization in the per-sample averaging and (ii) the std normalization inside the group baseline. Dr. GRPO removes these terms to produce an unbiased estimator and better token efficiency.

Fixes:

1) No length normalization: replace length-dependent denominators (e.g., masked means over variable token counts) by a fixed generation budget when averaging token losses, so gradients don’t scale up with longer outputs.

2) No std normalization in the group baseline: use the uncentered, group-mean–subtracted advantage

\[A^{(i)} \;=\; R^{(i)} - \frac{1}{G}\sum_{j=1}^G R^{(j)},\]avoiding variance-scaling that biases toward long responses.

These simple modifications yield unbiased policy gradients and curb runaway length while preserving reasoning accuracy, with ablations isolating each bias term.

Where it fits. Dr. GRPO is a drop-in replacement for GRPO in R1-Zero–style training recipes; code and plots show improved token efficiency and competitive AIME results at small compute.

GSPO: Group Sequence Policy Optimization

Motivation. Token-wise ratios in PPO/GRPO cause length-dependent variance and instability for long chains and MoE models. Rewards are sequence-level, so off-policy correction and clipping should be sequence-level too.

Objective (sequence ratio, sequence clip). Define a length-normalized sequence ratio

\[S^{(i)}(\theta) \;=\; \exp\Big(\tfrac{1}{|y^{(i)}|}\sum_{t=1}^{|y^{(i)}|}\log \tfrac{\pi_\theta(y^{(i)}_t\mid x,y^{(i)}_{<t})}{\pi_{\text{old}}(y^{(i)}_t\mid x,y^{(i)}_{<t})}\Big) \;=\; \Big(\tfrac{\pi_\theta(y^{(i)}\mid x)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(y^{(i)}\mid x)}\Big)^{1/|y^{(i)}|},\]and optimize a sequence-level clipped surrogate $\min\big(S^{(i)}A^{(i)},\;\mathrm{clip}(S^{(i)},1-\epsilon,1+\epsilon)A^{(i)}\big)$, optionally with group sampling. This aligns the control variate and clipping granularity with sequence rewards, stabilizing long-context RL and improving infra fit.

CISPO: Clipped Importance Sampling Policy Optimization

Motivation. Token-clip surrogates can zero gradients for many tokens (“masked-out” regions), wasting data under off-policy drift. CISPO instead clips the IS weights themselves, keeping gradient flow for all tokens/sequences.

Objective (weight clip).

\[\begin{aligned} J_{\text{CISPO}}(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{(q,a)\sim D,\ \{o_i\}_{i=1}^G \sim \pi_{\text{old}}(\cdot \mid q)} \Bigg[ \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^{G} |o_i|} \sum_{i=1}^{G}\sum_{t=1}^{|o_i|} \operatorname{sg}\!\big(\,\hat r_{i,t}(\theta)\,\big)\;\hat A_{i,t}\; \log \pi_\theta\!\big(o_{i,t}\mid q, o_{i,<t}\big) \Bigg], \\[4pt] \hat r_{i,t}(\theta) &= \mathrm{clip}\!\big(r_{i,t}(\theta),\ 1-\epsilon_{\text{IS,low}},\ 1+\epsilon_{\text{IS,high}}\big), \qquad r_{i,t}(\theta)= \frac{\pi_\theta(o_{i,t}\mid q, o_{i,<t})}{\pi_{\text{old}}(o_{i,t}\mid q, o_{i,<t})}. \end{aligned}\]Reported benefits: higher sample efficiency and stable large-scale RL in MiniMax-M1.