KL Regularization in LLM RL: Estimation and Optimization

Background

KL regularization is a default stabilizer in LLM reinforcement learning. We optimize for reward while penalizing deviation from a reference policy. In practice, once we move from the mathematical objective to an implementable loss, we face multiple choices that can change both stability and what gradient we actually take. This blog visits (1) the estimator for KL divergence, and then (2) the optimization of KL divergence. The discussion draws on Schulman’s note on KL approximation, and some recent work (1, 2, 3).

Part 1: Estimating KL from samples

The quantity we want

Let $p$ and $q$ be two distributions over the same space $\mathcal X$. We want the forward KL

\[\mathrm{KL}(q\|p)=\mathbb E_{x\sim q}\Big[\log\frac{q(x)}{p(x)}\Big].\]Define the ratio

\[r(x)=\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}.\]Then

\[\mathrm{KL}(q\|p)=\mathbb E_{x\sim q}\big[-\log r(x)\big].\]Computing this expectation analytically is generally intractable. We therefore turn to Monte Carlo estimators using samples $x\sim q$.

Estimator $k_1$: unbiased, high variance

The naive single sample estimator is

\[k_1(x)=\log\frac{q(x)}{p(x)}=-\log r(x).\]It is unbiased:

\[\mathbb E_{x\sim q}[k_1(x)]=\mathrm{KL}(q\|p).\]The practical problem is variance. Although $\mathrm{KL}(q|p)\ge 0$, the sample value $k_1(x)$ can be negative for many samples. The empirical average then relies on sign cancellation, which tends to be noisy.

Estimator $k_2$: biased, lower variance, and often close to KL

A common alternative is

\[k_2(x)=\frac12\Big(\log\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}\Big)^2=\frac12(\log r(x))^2.\]It is always nonnegative and empirically often has much lower variance than $k_1$.

It is biased in general, but when $q$ is close to $p$, its expectation matches $\mathrm{KL}(q|p)$ up to second order. The reason is a Taylor expansion around $r=1$.

Derivation: Taylor expansion around r = 1

When $q$ is close to $p$, we have $r(x)\approx 1$. Write

\[r(x)=1+u(x),\]where $u(x)$ is small. Use the Taylor series

\[\log(1+u)=u-\frac{u^2}{2}+\frac{u^3}{3}+O(u^4).\]Then

\[k_1(x)=-\log r(x)=-\log(1+u) = -u+\frac{u^2}{2}-\frac{u^3}{3}+O(u^4).\]For $k_2$,

\[k_2(x)=\frac12(\log r(x))^2=\frac12(\log(1+u))^2.\]Let $L(u)=\log(1+u)=u-\frac{u^2}{2}+\frac{u^3}{3}+O(u^4)$. Squaring and keeping terms up to cubic order:

\[L(u)^2 = \Big(u-\frac{u^2}{2}+\frac{u^3}{3}+O(u^4)\Big)^2 = u^2-u^3+O(u^4).\]So

\[k_2(x)=\frac12u^2-\frac12u^3+O(u^4).\]Now take expectation under $q$. The key identity is

\[\mathbb E_{x\sim q}[r(x)]=\mathbb E_q\Big[\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}\Big]=\int q(x)\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}dx=\int p(x)dx=1.\]Therefore

\[\mathbb E_q[u]=\mathbb E_q[r-1]=0.\]So the first order term in $\mathbb E_q[k_1]$ vanishes, giving

\[\mathbb E_q[k_1] = \frac12\mathbb E_q[u^2] -\frac13\mathbb E_q[u^3] +O(\mathbb E_q[|u|^4]),\]while

\[\mathbb E_q[k_2] = \frac12\mathbb E_q[u^2] -\frac12\mathbb E_q[u^3] +O(\mathbb E_q[|u|^4]).\]They share the same leading second order term $\frac12\mathbb E_q[u^2]$ and only differ at cubic and higher order. This is why $k_2$ can have low bias when KL regularization keeps $q$ close to $p$.

Estimator $k_3$: nonnegative and still unbiased

There is also a useful estimator that is always nonnegative and remains unbiased:

\[k_3(x)=(r(x)-1)-\log r(x).\]Nonnegativity is immediate from $\log r\le r-1$ for all $r>0$:

\[k_3(x)\ge 0.\]Unbiasedness follows from the identity $\mathbb E_q[r]=1$ used earlier: the $(r-1)$ term has zero mean, leaving $\mathbb E_q[k_3]=\mathbb E_q[-\log r]=\mathrm{KL}(q|p)$.

So $k_3$ preserves the correct mean like $k_1$, but avoids negative samples like $k_2$.

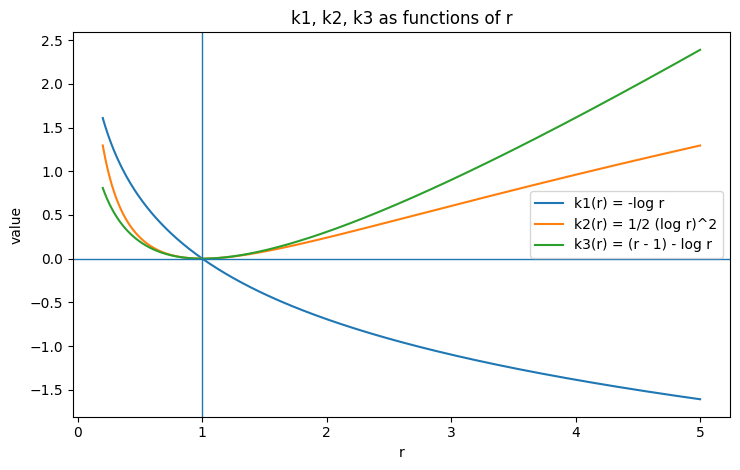

Visual intuition

A few qualitative takeaways:

- $k_1(r)=-\log r$ crosses zero at $r=1$ and becomes negative for $r>1$.

- $k_2(r)=\frac12(\log r)^2$ is always nonnegative.

- $k_3(r)=(r-1)-\log r$ is always nonnegative and is unbiased for KL under samples from $q$.

Part 2: Optimizing KL regularization

This section derives the KL gradient, then analyzes what happens when we differentiate $k_1$, $k_2$, and $k_3$ directly. We will show that the Direct term of $k_2$ gives the oracle gradient.

Gradient of an expectation under the sampling distribution

For a function $f(x,\theta)$ with $x\sim\pi_\theta$, the gradient identity is

\[\nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{x \sim \pi_\theta}[f(x, \theta)] = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim \pi_\theta}\big[\underbrace{f(x, \theta)\,\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(x)}_{\text{REINFORCE}}+\underbrace{\nabla_\theta f(x, \theta)}_{\text{Direct}}\big].\]The first term is named after the classic REINFORCE algorithm: it uses the score function $\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta$ to propagate credit through the sampling process. The second term is what you get if you treat samples as fixed and differentiate $f$ directly—we call it the Direct term.

In vanilla policy gradient, $f(x, \theta)$ is essentially the reward function $R(x)$ that does not depend on $\theta$, so the Direct term vanishes and only the REINFORCE term survives.

Applying to KL

For KL divergence, set $f(x,\theta)=\log\pi_\theta(x)-\log\pi_{\rm ref}(x)$. Substituting into the identity gives two terms above. The second term $\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(x)$ vanishes in expectation (since $\int\nabla_\theta\pi_\theta(x)\,dx=\nabla_\theta 1=0$), leaving only the first term:

\[\nabla_\theta\,\mathrm{KL}(\pi_\theta\|\pi_{\rm ref}) = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}\big[ (\log\pi_\theta(x)-\log\pi_{\rm ref}(x))\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(x) \big].\]Using the ratio $r(x)=\pi_{\rm ref}(x)/\pi_\theta(x)$:

\[\nabla_\theta\,\mathrm{KL}(\pi_\theta\|\pi_{\rm ref}) = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}\big[ (-\log r(x))\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(x) \big].\]This has the same form as a policy gradient with “reward” $-\log r(x)$. When $r<1$ (policy assigns more mass than reference), the coefficient is positive and the gradient reduces that probability; when $r>1$, the coefficient is negative and the gradient increases it.

Full gradient of $k_2$

For $k_2(x)=\tfrac12(\log r(x))^2$, consider both terms in the gradient identity:

Direct term:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[\nabla_\theta k_2]=\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[(-\log r)\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta]=\nabla_\theta\mathrm{KL}(\pi_\theta\|\pi_{\rm ref}).\]This equals the oracle gradient.

REINFORCE term:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[k_2\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta]=\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}\big[\tfrac12(\log r)^2\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta\big].\]This does not simplify further. So the full gradient of $k_2$ is the oracle gradient plus an extra REINFORCE term. If we keep only the Direct term (ignoring the REINFORCE term), we recover the oracle gradient exactly.

Full gradient of $k_3$

Write $k_3(x)=(-\log r(x))+(r(x)-1)$ and analyze each part.

Part 1: $(-\log r)$

-

Direct:

\(\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[\nabla_\theta(-\log r)]=\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta]=0\).

-

REINFORCE:

\(\mathbb{E}_{x\sim\pi_\theta}[(-\log r)\,\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta]=\nabla_\theta\mathrm{KL}(\pi_\theta\|\pi_{\rm ref})\) (oracle gradient).

So the $(-\log r)$ part contributes exactly the oracle gradient via REINFORCE, just like $k_1$.

Part 2: $(r-1)$

- Direct:

This is the reverse KL gradient. (The third step uses importance sampling)

- REINFORCE:

This is negative reverse KL gradient—it exactly cancels the Direct term!

Summary for $k_3$:

| Term | Direct | REINFORCE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| $-\log r$ | $0$ | forward KL | forward KL |

| $r-1$ | reverse KL | $-$reverse KL | $0$ |

| $k_3$ | reverse KL | forward KL $-$ reverse KL | forward KL |

With full gradients, $k_3$ gives the correct forward KL gradient. But with only the Direct term, the $(r-1)$ term no longer cancels and we get the reverse KL instead.

Practical fix: straight-through estimator

The analysis above suggests a practical solution: use any unbiased estimator ($k_1$, $k_3$, etc.) for the value, but route gradients through $k_2$ to get the correct KL gradient. This is exactly what verl implements:

def kl_penalty(logprob, ref_logprob, kl_penalty):

forward_score = kl_penalty_forward(logprob, ref_logprob, kl_penalty)

if not kl_penalty.endswith("+") or kl_penalty in ("mse", "k2"):

return forward_score

# Straight-through: value from forward_score, gradient from k2

backward_score = 0.5 * (logprob - ref_logprob).square()

return backward_score - backward_score.detach() + forward_score.detach()

The trick backward_score - backward_score.detach() + forward_score.detach() returns forward_score in the forward pass but routes gradients through backward_score (which is the Direct term of $k_2$). This gives unbiased KL gradients regardless of which estimator is used for the value.